Three Cups of Tea

Issue 77 February 2011

In one of life’s strange twists of fate, a failed climber becomes a great humanitarian. Salma Hasan Ali tells the extraordinary story of Greg Mortenson and his passion to build schools in Pakistan

and Afghanistan.

Nasreen sits on the floor of her two-room apartment in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, a patterned red shawl gently draped over her hair. The only piece of furniture in the room is a small table with a computer, covered with layers of blankets. Her three young children, torn between curiosity and shyness, surround her as she discusses her daily routine, her dreams for her kids and her desire for education. She has a gentle grace, a serene disposition, but her eyes - heavy, settled, soulful - betray the difficult journey she has endured.

Nasreen grew up in a tiny village in the northernmost part of Pakistan. Although one of the brightest students in school, in a region where few girls have the opportunity to learn to read and write, the unexpected death of her mother when she was 12 forced her to drop out to take care of her four younger siblings and her blind father. “When my mother died, all my dreams went far away,” she says. But she continued to study, on her own, late at night, and in 1995 at the age of 15, became one of the first girls in the region to receive her metric diploma.

Greg Mortenson met Nasreen in her village in 1999 and promised to help her fulfill her dream of becoming a maternal health care provider. His organisation, the Central Asia Institute (CAI), offered her a scholarship to study in Rawalpindi. Eight years later, village elders allowed Nasreen to leave the village. Today, she is completing her medical assistant degree and wants to get an ob-gyn nursing diploma. She hopes to work in areas even more remote than her own to teach other women what she has learned. “I am very happy,” she tells me as we look at family photographs. “I’ve been given a chance to fulfill my dreams. I want to give my children the best education, so they can fulfill theirs too.”

Mortenson has been helping girls get an education in remote, sometimes volatile, parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan for the past 18 years. CAI has built or supported more than 170 schools, mainly for girls, providing education to more than 68,000 children. It also supports women’s literacy centres and maternal healthcare programs, and provides higher education scholarships for bright young women like Nasreen. “Watching that first brave girl enter a school is like watching man taking his first step on the moon,” says Mortenson.

Mortenson’s journey to educate girls began with a failed attempt to summit K2 in 1993. He had set out to scale the world’s second highest peak to honour his sister who had died of epilepsy. After 78 days on the mountain, and just 600 metres from the top, Mortenson turned back to help a fellow climber who had fallen ill. After ensuring his safety, Mortensen himself got lost and stumbled onto a tiny Pakistani village so isolated and poor that one in every three children died before the age of one. Sick and emaciated, Mortenson was nursed back to health by the Muslim villagers. They shared their meager possessions with him—putting the little sugar they had in his cup of tea, covering him with their warmest blanket.

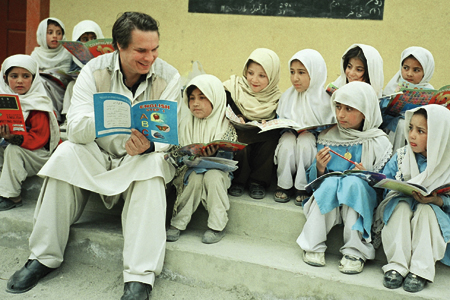

Greg Mortenson with Khanday schoolchildren, Pakistan.

Overwhelmed by their hospitality, Mortenson wanted to repay their kindness. He gave away the few possessions he had and used his medical training to treat minor illnesses. Just before he left, he saw 82 children sitting in the dirt writing with sticks in the sand. The village did not have a school, and could not afford the $1-day salary for a full time teacher. He made a promise to return and build a school.

Back in the United States, he wrote 580 letters to sports stars and celebrities to raise the $12,000 he needed to build a school. He got one cheque - for $100. Mortenson worked double shifts, briefly living in his car before selling it, along with his mountaineering equipment, to raise funds. When his mother, an elementary school principal, invited him to speak to her students, the children decided to help. They collected over 62,345 – in pennies! Mortenson eventually raised the funds, returned to the village and built a five-room school in the summer of 1997. He continues to build schools in northern Pakistan and Afghanistan.

I first met Mortenson four years ago in Washington, DC when he was launching his book “Three Cups of Tea”, which chronicles his journey. Captivated by his story and his commitment to girls’ education in the country of my origin, I wanted to see for myself how this soft-spoken, six-foot-four American from the Midwest is able to navigate within my culture with such grace and sensitivity. In 2009, when Mortenson was receiving Pakistan’s highest civilian award, the Sitara-e-Pakistan, I had the chance to visit his schools, meet his local team, and see him in his element.

When we arrived at the Gundi Piran Girls’ School in Patika, in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, about 20 girls in light gray shalwar kameezes and maroon shawls are finishing their exams in an open-air classroom, in the centre of which is a rectangular dirt patch with seven gravestones. The school is located near the epicentre of the 7.6 magnitude earthquake that devastated Kashmir in October 2005, killing more than 80,000 people and displacing 3.5 million. Thousands of schools were destroyed, and CAI has rebuilt several in the area. Today, 350 girls attend this one-story, 12-room school that includes a library, computer room and playground. “I never thought I would ever go back to school,” says Sadia, 18, who is now deciding whether to become a doctor or a teacher.

“You can drop bombs, build roads, put in electricity, but until girls are educated, society won’t change,” Mortenson says. He quotes economists who highlight the benefits of educating girls to at least a fifth grade level: drop in maternal and infant mortality rates, as girls know how to better take care of themselves and their babies; decrease in population rates, as they are more likely to marry later and have fewer children; and healthier and more educated families, as mothers pass on the importance of education.

Kashmiri refugees in school, Pakistan.

In a region where educating girls is not a priority and where girls’ schools are often targeted, Mortenson has been able to convince conservative elders to educate their daughters. He invokes Islam to emphasise the importance of education. “The first word revealed in the Quran is ‘iqra’, which means to read, and the first two chapters implore people to seek knowledge,” says Mortenson. He recalls the time when a fatwa was issued against him. But when his work was assessed, a letter arrived from the Supreme Council in Iran saying, “Dear Compassionate of the Poor, our Holy Qur’an tells us all children should receive education, including our daughters and sisters. Your noble work follows the highest principles of Islam.”

The process to build a school can sometimes take years. In one village, it took eight years to persuade the local council to allow a single girl to attend school. By the time the school opened in 2007, there were 74 girls enrolled. One year later, the number had tripled. Other times, elders need no convincing, like the two members on the village education committee who greeted us at a school in the Punjab region. “The era of not sending girls out of the home is over. Girls need to know how to function in society,” they said. One of the elders, about 70, in a white kurta pajama and turban, captured the value of educating a girl, “When one girl becomes educated, then one family becomes educated. Her children benefit, her parents benefit, her brothers and sisters benefit.” The sentiment echoes an African saying Mortenson learned growing up in Tanzania, which drives much of his work: “Educate a boy and you educate an individual. Educate a girl and you educate a community.”

Mortenson has spent more than 70 months in Pakistan and Afghanistan walking for miles and sitting in the dirt talking to villagers. In each village, he asks the mothers how he can help them. They respond, “We want our children to go to school.”

Azerha with her children in Korphe Village, Pakistan.

For every rupee that CAI invests in building a school, the village has to match it by providing free labour, wood, land, and cement. Those too old or weak to provide labour make tea for the team or their children pay a small tuition. “From day one we make sure the school belongs to each and every person in the community.” Perhaps that is why only one CAI school has been attacked by the Taliban. Even then, the local militia leader, who has two daughters in another school, defended the school with the help of others, and it reopened two days later.

“It’s about building relationships, listening to people, and drinking a lot of tea,” Mortenson says. “Tea drinking is one of the main hazards of my job,” he jokes. He has had tea with the Taliban, religious clerics, tribal chiefs, village elders, militia leaders, conservative fathers, intimidated teachers and nervous children. Mortenson quotes a Balti saying he learned from his mentor, which inspired the title of his book: “The first cup of tea, you’re a stranger. The second cup, you become a friend. And by the third cup, you’re family.”

Mortenson attributes his ability to work between two cultures to his childhood growing up in Tanzania where his parents were teachers. “It was a diverse environment,” he says, “my closest friends were Muslims and Hindus and kids of all backgrounds.” This is where he first learned about Islam. He recalls the time he went to the top of the minaret to hear the muezzin announce the call to prayer. “Islam is about tolerance,” says Mortenson, “a few people have hijacked this.” On September 11, 2001, Mortenson was near the Afghan-Pakistan border and remembers the outpouring of sympathy from villagers. “Little old ladies brought me eggs to give to the widows in New York.”

“The real enemy, whether it’s in Africa or Afghanistan or in the US, the real enemy is ignorance, and it’s ignorance that breeds hatred,” Mortenson says at the end of each of his talks. “To overcome ignorance, we need to have courage, we need to have compassion, and most of all, we need to have education.”

Mortenson’s passion for educating children is ever-present. On our last day in Pakistan, after being awarded the Sitara-e-Pakistan in a formal ceremony at the President’s House, we went to a ramshackle teahouse to celebrate. A young boycame over and sat next to Mortenson on the tottering wooden bench. The boy couldn’t speak and was hard of hearing. Regardless, Mortenson picked up some stones, held them in his palm, and started giving the boy a math lesson.

Three Cups of Tea, by Greg Mortenson and David Oliver Relin

Stones into Schools, by Greg Mortenson

images courtesy of Central Asia Institute

To read the feature in its entirety, pick up a copy of our latest issue by subsribing here -

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

1 Comment

1

Hasna

7 Feb 11, 13:24

Salams,

I am so glad to see this article. I have read both books and am truly inspired by this man. May Allah guide him to Islam. Ameen