Burma - A Forgotten Battle

Issue 62 November 2009

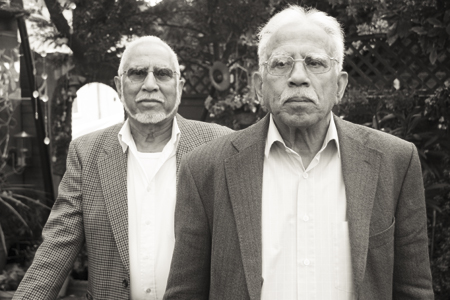

Commonwealth soldiers fought in campaigns across the globe, but these contributions are rarely acknowledged, as they are generally referred to as British Operations. We hear from veteran brothers Mushtaq Ahmed and Abdul Salam about Britain’s forgotten battle– Burma – where 700,000 Indian soldiers were posted during the Second World War, out of a total Allied force of 1 million. The Japanese fought fiercely, and jungle warfare had an immense psychological impact on the soldiers. Prisoners of war were in particular treated very badly and many were made to join the Indian National Army and fight against their compatriots.

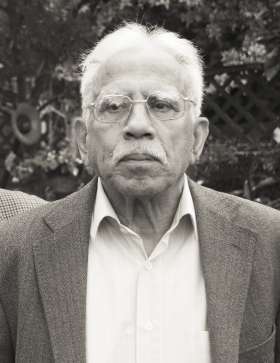

Abdul Salam, aged 84

I was 16 when I enlisted. I had joined a political youth party aged 12 where they were always talking about fighting for the British and seeking out your own independence. The sense of duty appealed to me and I had always enjoyed sport more than school so I thought it would be perfect for me.

Training was intense. We’d crawl on the ground for hours, pulling ourselves along the dirt and gravel by our elbows and forearms. They’d wake you up at 12, sometimes 1am to start the day and you’d have to learn to function on very little sleep. During training, I’d run anywhere between 20-25 miles a day. The Sikhs in my regiment would complain to the commanding officer, saying that I used black magic to channel strength. I trained religiously. It was all I ever thought about. Our running course was my favourite, with marks of 100, 220, 440, 880 and 1 mile. I’d sprint and do hurdles every single day to keep myself physically agile.

I was posted in Rangoon as part of the 2nd Patiala regiment, on ordinance duty, taking inventory in nearby storage camps, and transporting supplies wherever they were needed.

There were 90 divisions of 10,000 soldiers; a mixture of Caucasians, Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus and Africans. Many of us were on foot, walking through battlegrounds – encountering showers of bullets from overhead and grenades going off around us. But the colonel would bellow, ‘Advance!’ and we’d have to advance. Men went forward, died, and another regiment was sent right in after them.

The Japanese bombed and buried many of the vital roads we needed to transport supplies. I remember swimming through dams and rivers. Those who didn’t know how to swim drowned. Even those who could were in danger of losing control because of the powerful tides. I remember seeing a soldier swallowed up by a wave once and smacked against a boulder. He lost his arm in that incident but I saw him not too long after, bandaged up and ‘advancing’.

There was continuous gunfire. The stench of bodies in the jungle was simply vile. Each day I clung to the thought about finishing the next day so you were one step closer to freedom, to home.

Many civilians in Vietnam were Muslims. I remember walking through a busy town centre in Rangoon once when the area came under attack by Japanese planes. I found a small girl, standing alone crying. I lifted her up and started to run, when I heard a man call out from a doorway. I realised it was her father, so I ran back to hand him his daughter but he pulled me into the house as well. When he asked if I was Muslim I replied, ‘alhamdu-llilah’, and he took me straight into the bunker for protection. They were a lovely family.

When we left for Burma there were so many of us. And when we returned, there were only twelve of us. On the journey back, I tried to recount what had happened to them, but I just didn’t know.

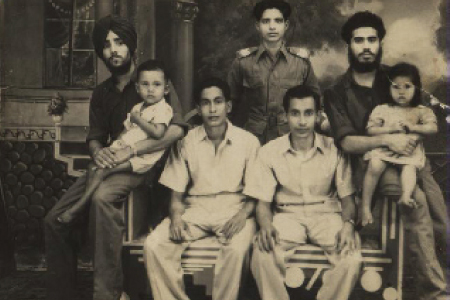

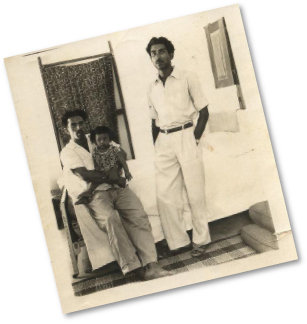

Abdul Salam (far right) is pictured with the family of the girl he saved during the Japanese attack.

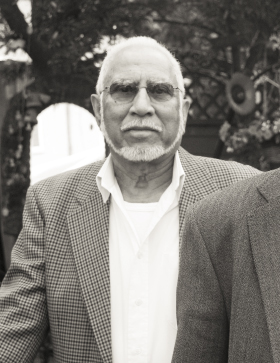

Mushtaq Ahmed, 83

My older brother was already in the army and his letters were always full of excitement and adventure. At the age of 14 I joined the ‘boys’ division, and was sent off for training that same day. Within a few hours, I found myself at the Gurdaspur station, eating daal-roti and waiting for a taxi to take me to Lahore. At the induction, I was sent off to the Nasik training camp where to my surprise, everyone in the Indian National Army was made to wear a ‘pughri’, a Sikh headdress, regardless of religion.

My initial training was in weaponry. I learnt how to use a rifle, a machine gun, then a Tommy gun and finally 37metre calibre guns. These were massive; they used them to gun down planes. Unfortunately for us, the Japanese were so much more advanced in their technology. They were aware that we had the predictor guns, so they pretty much avoided the air space being monitored.

Recognising I was good at coordinates, the officers trained me in code-breaking. For six months, I was taught how to read coded telegraphs. I can’t explain how difficult that was. I didn’t even know how to read a map properly! But all of that came with time and practice. The compass was the only thing I had trouble with; it always read north, no matter which direction I pointed! Then I learned how to read all the other directions. The compass was the only thing I had on me in the jungle to determine the qiblah, so I think God put it into my head that it was imperative to learn.

After almost two years of training, I was posted in Burma in 1941. I was assigned to the ‘observer post’; scouting ahead of the battalion with an officer and a driver, all the while trying to remain undetected, in order to estimate how far the enemy was from us from the position of where they dropped their bombs. As bombs would come from overhead, I’d watch see them soar through the sky above us and land on those exact coordinates I punched in.

As far as I knew back then, I was doing my duty. I was finally responsible for something big. I had something of my own and I did it with complete commitment and strength. I know enough now to realise that we were all pawns.

It rained in Rangoon every, damn day. And it wasn’t like the pretend rain you get over here, it was heavy torrential rain. It would just wipe away everything. The make shift huts, the odd stretcher we’d use to sleep on – just everything. Yet I was grateful for it – it was the same water we drank then.

After the war ended, and I finally journeyed back home, I peered out of the jeep and saw the streets lined with corpses. The India-Pakistan conflict had already begun and I could see the result of it in the blood-smeared town that I had once called home. It was horrifying. I was embarrassed of all of us, the Muslims, the Hindus and the Sikhs for not recognising that we had all long fought together, united in the face of the enemy.

------------------------------------------------------------------

< Return to Main Article

Medals of Honour

We select a number of high profile Muslim servicemen and women who were awarded decorated military honours for their dedication and relentless commitment to their detachment.

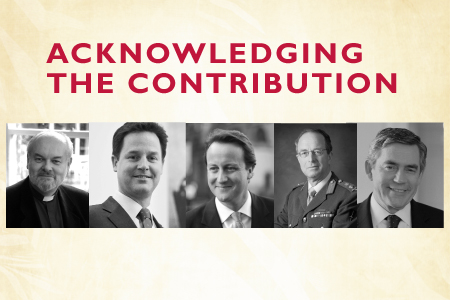

Acknowledging the Contribution

Political, Military and Religious leaders pay tribute to the sacrifices made by Muslims for Britain in the two world wars.

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments